Table of Contents

Ruth Ellis

Ruth Ellis, originally born Ruth Neilson, entered the world in Rhyl, Denbighshire, Wales, on October 9, 1926, she was the fifth child among six siblings. Her family’s journey led them to Basingstoke, Hampshire, England, during her early years.

Within her family background, a rich tapestry emerged: her mother, Elisaberta (Bertha) Goethals, a Belgian war refugee, and her father, Arthur Hornby, a skilled cellist hailing from Manchester. The official records of marriage note Arthur Hornby’s union with Elisa B. Goethals at Chorlton-cum-Hardy in the year 1920. As time progressed, Arthur chose to adopt the surname Neilson subsequent to the birth of Ruth’s elder sister, Muriel, in 1925.

Muriel Jakubait holding a picture of her sister Ruth Ellis when she was 24 years old.

In 1928, when Ruth had reached the tender age of two, the fabric of their lives encountered a sombre note as tragedy struck. Arthur’s twin brother, Charles, who met his fate in a bicycle collision with a steam wagon.

According to Muriel, Arthur became physically and sexually abusive shortly after his brother’s death, with Bertha being aware of the abuse but taking no action.

The sexual abuse eventually resulted in Muriel conceiving a child by her father at age 14, which led to Arthur being questioned, and ultimately released, by police; the child, a son, was brought up as a sibling to the other children.

Arthur turned his attention towards Ruth after Muriel reached puberty, but Ruth continually resisted the abuse.

Ruth briefly attended Fairfields Senior Girls’ School in Basingstoke, leaving when she was aged 14. She found work as an usherette at a cinema in Reading, Berkshire.

Shortly afterwards, in 1940, Arthur moved to London after being offered the live-in position of caretaker-chauffeur for Porn & Dunwoody Ltd, a lift manufacturer. The following year, while her older brother Julian was on leave from service in the Royal Navy, Ruth befriended his girlfriend, Edna Turvey, who introduced her to what Muriel later called “the fast life.”

Ruth and Edna eventually moved to London and lodged with Ruth’s father. He continued his abuse of Ruth while engaging in an affair with Edna, which ended when Bertha made an unannounced visit and caught the pair in bed. Bertha herself moved to London soon afterward.

In 1944, 17-year-old Ruth became pregnant by a married Canadian soldier named Clare Andrea McCallum. She was subsequently forced to move to a nursing hospital in Gilsland, Cumberland, where she gave birth to a son named Clare Andria Neilson, also known as “Andy”, on September 15.

The father sent money for about a year, then stopped. Andy eventually went to live with Bertha, while Ruth supported her son by working in several factory and clerical jobs.

Not earning much,, Ruth answered an advertisement for a job as a photographer’s model. She would have to work at night at a private club on Manchester Square in London’s respectable Marylebone district close to the shoppers’ “Mecca” of Oxford Street.

The job entailed having to pose in the nude for the club’s members to snap her with their Brownie Box cameras. In order to look good she stopped wearing glasses, preferring to observe the world through a misty cloud.

The club was appropriately called the Camera Club. When she got home in the early hours of the morning, Arthur, who had suffered a stroke, would despite a speech impediment, shout at her that she was a slut.

He was not referring to her job, but to her life in general – the fact that she had had an affair with a married man who had walked out on her and left her with a child. It was Ruth’s earnings – £1 an evening plus commission on what the men in her company drank – which kept him and Bertha from the poorhouse, but which he did not acknowledge.

Through her work at the Camera Club, Ruth met a man named Morris Conley, known as Maurie Conley. Conley was the owner of several private men’s clubs. Those were the kind where men went after work in search of drink and sex.

On November 8, 1950, Ruth married George Ellis, a 41-year-old divorced dentist and father of two sons. The ceremony took place at the register office in Tonbridge, Kent.

Notably, George had been a patron at the Court Club. However, the union proved tumultuous due to George’s alcoholism, jealousy, and possessiveness. Their relationship quickly deteriorated as he grew increasingly convinced of her involvement in extramarital affairs. Despite periodic separations initiated by Ruth, she found herself drawn back into the marriage time and again.

In 1951, during her fourth month of pregnancy, Ruth made an uncredited appearance as a beauty queen in the Rank film “Lady Godiva Rides Again.” This cinematic piece featured notable actors like Dennis Price and Dana Wynter.

During her time on set, Ruth formed a close bond with Diana Dors, the star of the production. Following the birth of her daughter Georgina, Ruth found herself in a challenging situation as George, the child’s father, denied paternity. This led to their separation shortly after Georgina’s birth. Ruth and her daughter took up residence with her parents, where she resumed her work as a hostess to ensure financial stability.

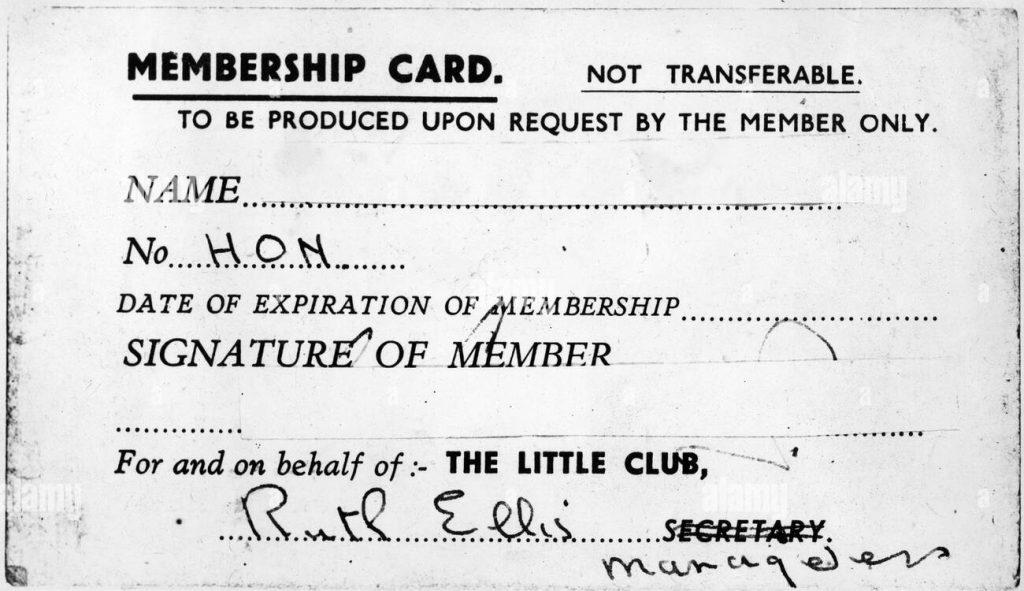

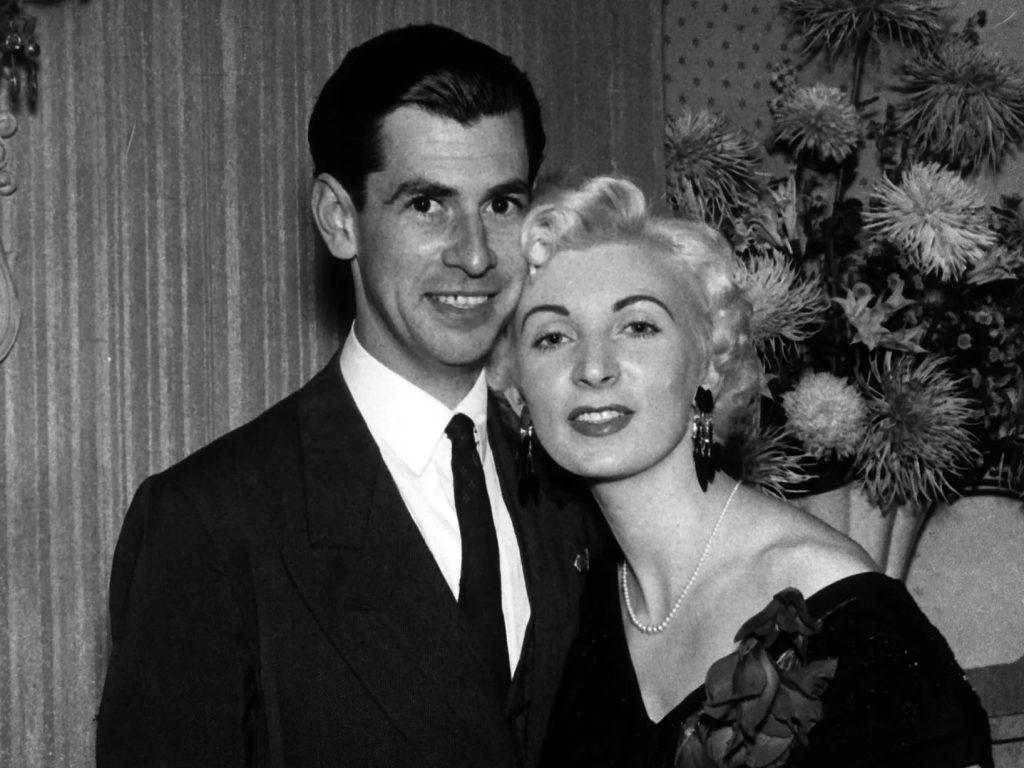

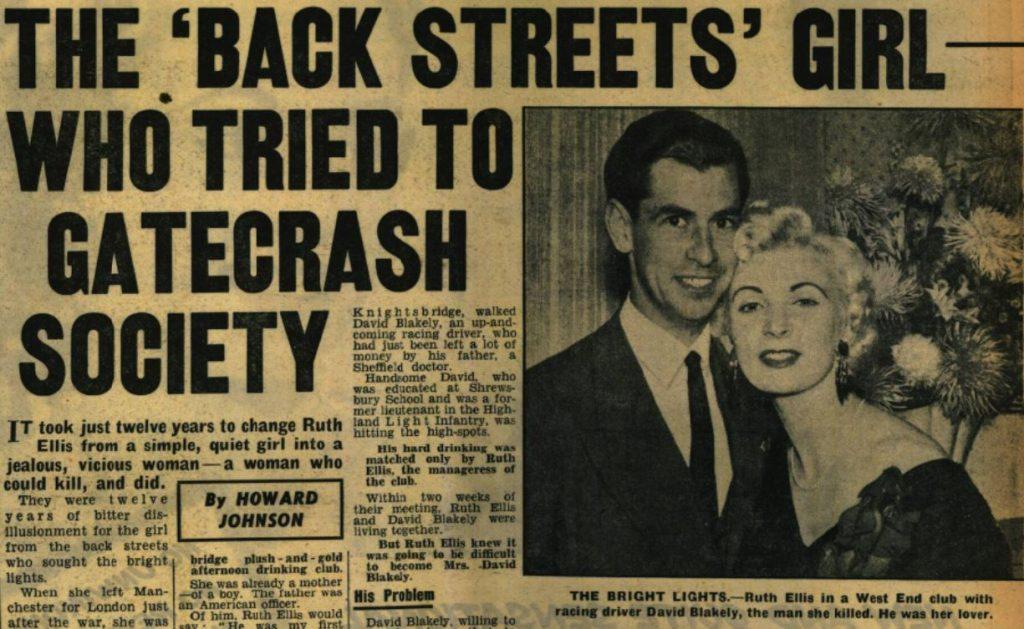

In 1953, Ruth assumed the role of manager at the Little Club in Knightsbridge. During this period, she was bestowed with opulent gifts from admirers and cultivated numerous friendships with celebrities. It was during this time that she crossed paths with David Blakely, a man three years her junior, introduced to her through the racing driver Mike Hawthorn.

David Blakely

Born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, in 1929, David Blakely emerged as one of the four offspring of John Blakely, a Scottish medical practitioner, and his Irish spouse Annie, hailing from Ballynahinch. Alongside him were two brothers, Derek Andrew Gustav and John Brian, as well as a sister named Maureen.

The year 1940 marked the divorce of his parents, leading to his mother’s subsequent marriage to Sir Humphrey Wyndham Cook, a notable figure as a co-founder of ERA (English Racing Automobiles) alongside Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon, with the establishment taking root in Bourne, Lincolnshire, back in November 1933.

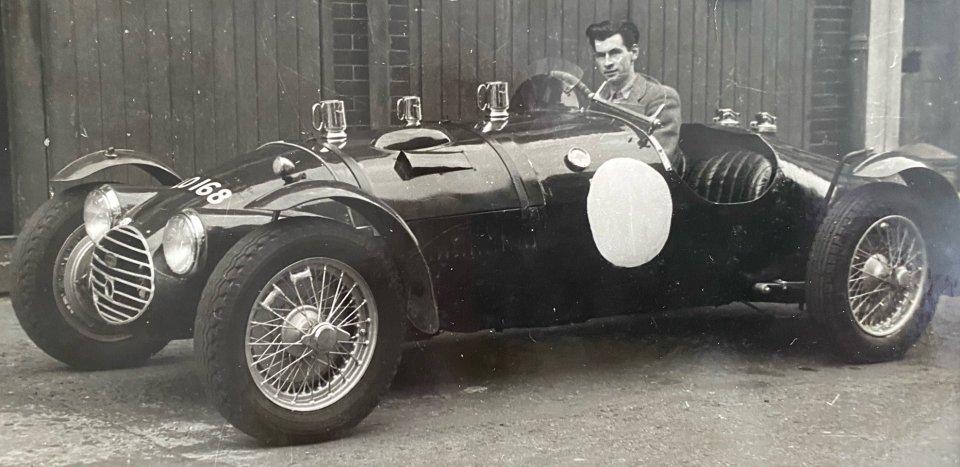

Following his tenure in the Highland Light Infantry for National Service, David Blakely’s path evolved into that of a passionate race car driver. The early 1950s witnessed his participation in racing endeavours, achieving commendable outcomes while piloting a HRG sportscar initially, and later a Leonard – MG. A pivotal moment arrived in 1954 when he decided to channel his utmost efforts into crafting a novel automobile, christened the HRG Emperor.

David Blakely with HLO 168 and Silverstone trophies

Collaborating with a former Aston Martin engineer by the name of Anthony “Ant” Findlater, Blakely’s vision materialized into a vehicle featuring a twin-cam 1.5-litre Singer engine. The construction boasted a tubular chrome-steel chassis, VW front suspension, de Dion rear end, and a full-width aluminium body, exuding an aura reminiscent of a Ferrari “Monza.”

The debut of the HRG Emperor unfolded at the 1954 Boxing Day Meeting held at Brands Hatch, where Blakely’s prowess secured him a commendable second place, trailing behind John Coombs in a Lotus MKVIII – Connaught.

Buoyed by its impressive inaugural performance, the HRG Emperor, alongside its accomplished driver, commanded the limelight within the British media. The subsequent year, 1955, witnessed collaborative efforts between David Blakely and Ant Findlater as they meticulously refined the vehicle for the upcoming season, even contemplating a limited production run.

Despite being primarily recognized for his racing accomplishments and opulent lifestyle, Blakely’s abilities led to his recruitment by Bristol Motor, where he took the wheel of one of the two factory-backed Bristol 450 sportscars enlisted in the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans event scheduled for June that year. But before the opening event of the season, David Blakely was dead.

Murder

Within weeks of meeting Ruth David Blakely moved in to Ruth’s flat above the club despite being engaged to another woman, Mary Dawson. She had a passionate and tempestuous relationship with David Blakely with whom she often quarrelled. Ruth endured a substantial amount of severe abuse at the hands of David Blakely throughout their relationship.

Ruth became pregnant for a fourth time but had her second abortion, feeling she could not reciprocate the level of commitment Blakely showed towards their relationship.

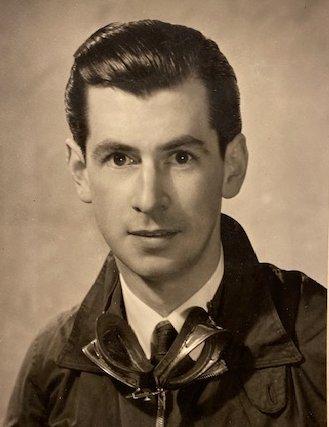

Subsequently, she started a relationship with Desmond Cussens. Born in 1921 in Surrey, Cussens had a notable history as an RAF pilot, flying Lancaster bombers during the tumultuous period of World War Two.

Following his service, he transitioned to the realm of accountancy in 1946. Cussens later became the director within the family enterprise, Cussens & Co, a wholesale and retail tobacconist with a notable presence encompassing London and South Wales.

With her managerial position at the Carroll Club terminated, Ruth found herself seeking new horizons. This led her to establish a residence at 20 Goodward Court, located on Devonshire Street to the north of Oxford Street. It was here that she became intertwined in an intimate affiliation with Cussens, assuming the role of his mistress.

At the same time the relationship between Ruth and Blakely continued, gradually becoming more hostile as they both ventured into new romantic connections. Despite the turmoil, Blakely proposed marriage, an offer to which Ellis agreed. In January 1955, Ellis suffered yet another loss, experiencing a miscarriage due to a physical altercation with Blakely, during which he punched her in the stomach.

On Easter Sunday, April 10, 1955, Ellis travelled by taxi from Cussens’s residence to a flat on the second floor of 29 Tanza Road in Hampstead.

The flat was the home of Anthony and Carole Findlater and was where she suspected Blakely might be found. Upon her arrival, she noticed Blakely’s car departing. Opting to confront the situation, she paid the taxi fare and walked approximately a quarter mile to The Magdala, a four-story pub on South Hill Park in Hampstead. There, she identified David’s vehicle parked outside.

Around 9:30 pm, David Blakely and his companion Clive Gunnell emerged from the Magdala. As Blakely walked by, Ellis, who had positioned herself near Henshaws Doorway, a newsagent adjacent to The Magdala, attempted to engage him with a greeting. Blakely, however, ignored her initial attempt. When she called out his name again, he finally acknowledged her presence.

While Blakely searched for his car keys, Ellis retrieved a .38 calibre Smith & Wesson Victory model revolver from her handbag and discharged five rounds at him. The initial shot missed its mark, prompting Blakely to flee. Ellis pursued him around the car, firing a second shot that brought him down to the pavement. Standing over him, she proceeded to fire three more rounds into his body. Notably, one of these shots was fired at incredibly close range, leaving visible powder burns on his skin.

The .38 Smith and Wesson revolver that killed David Blakely.

Witnesses observed Ellis standing transfixed near the fallen body, accompanied by the distinct sound of several clicks as she attempted to fire the revolver’s sixth and final bullet. Her efforts culminated in a shot fired into the ground, which unfortunately rebounded and struck Gladys Kensington Yule, 53, injuring her thumb as she walked toward The Magdala.

Gladys Yule arriving at the Old Bailey to give evidence in Ruth Ellis’ murder trial, Mrs Yule’s hand was wounded during the fatal shooting of David Blakely in Hampstead.

In a state of shock, Ellis implored Gunnell to call the police, acknowledging her guilt by stating, “Will you call the police, Clive?” Subsequently, she was promptly apprehended by off-duty police officer Alan Thompson (PC 389), who not only seized the still-smoking firearm but also heard her utter, “I am guilty, I’m a little confused.”

Transported to Hampstead police station, Ellis exhibited an appearance of composure, displaying no overt signs of intoxication or substance influence. During her time at the station, she provided a comprehensive confession to the authorities, resulting in her official charge of murder.

Meanwhile, Blakely’s body was transported to a hospital, bearing multiple gunshot wounds that had affected his intestines, liver, lung, aorta, and windpipe.

Ruth Ellis with David Blakely at the Little Club in London 1955

Trial

No solicitor accompanied Ellis during her interrogation or when she provided her statement at Hampstead police station. Curiously, although the night in question saw the presence of three police officers – Detective Inspector Gill, Detective Inspector Crawford, and Detective Chief Inspector Davies – no legal representative was by her side. This absence of legal counsel continued when she made her initial appearance at the magistrates’ court on April 11, 1955, where she was subsequently detained.

During her ordeal, Principal Medical Officer M. R. Penry Williams conducted two examinations but found no indications of mental illness. Furthermore, an electroencephalography examination on May 3 yielded no abnormal findings.

While held in Holloway on remand, Ellis underwent evaluations by two different psychiatrists: Dr. D. Whittaker, representing the defence, and Dr. A. Dalzell, acting on behalf of the Home Office. Both examinations concluded without any evidence suggesting insanity.

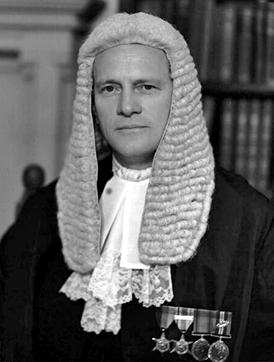

On Monday, June 20, 1955, Ellis took her place in the Number One Court at London’s Old Bailey, presided over by Mr. Justice Havers. Her attire consisted of a black suit paired with a white silk blouse, complementing her freshly bleached and carefully coiffured blonde hair.

She pleaded not guilty, apparently so that her side of the story could be told, rather than in any hope of acquittal. She particularly wanted disclosed the involvement of the Findlaters in what she saw as a conspiracy to keep David away from her.

Ellis was resolute in seizing her moment. However, her unwavering attachment to the brassy blonde persona contributed to the less-than-favourable impression she left on those present during her testimony in the courthouse.

It’s obvious when I shot him I intended to kill him.

Ruth Ellis, in the witness box at the Old Bailey, 20 June 1955

This constituted her response to the sole query presented to her by Christmas Humphreys, the prosecuting attorney. He inquired, “When you discharged the revolver at close proximity into David Blakely’s body, what was your intent?”

The defence counsel, led by Aubrey Melford Stevenson with support from Sebag Shaw and Peter Rawlinson, would have undoubtedly prepared Ellis for this anticipated question before the trial commenced, following the established norms of legal practice.

Her retort in the presence of Humphreys within the courtroom essentially ensured a guilty verdict, subsequently leading to the obligatory death sentence. The jury’s deliberation spanned a mere 23 minutes before reaching a conviction. As a result, she was handed down the sentence and subsequently confined to the condemned cell at Holloway.

It had taken a jury of 10 men and two women barely 23 minutes to find her guilty of killing her lover by emptying a revolver into him outside a London public house. And as Mr. Justice Havers put on the black cap, Mrs. Ellis, the mother of two children, turned to the prison nurse standing beside her and smiled gently. Then she turned and, with a wardress’s hand under her arm, walked calmly down the steps to the death cell.

The Manchester Evening News 21 June 1955

Execution

In a 2010 television interview, actor Nigel Havers, the grandson of Mr. Justice Havers, shared that his grandfather had penned a letter to the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George, advocating for a reprieve for Ruth Ellis due to his belief that the crime was a result of crime passionnel.

The family still retains the curt refusal from the Home Secretary. Additionally, there is a notion that a contributing factor to the final decision was the incident where Gladys Yule an innocent bystander was injured.

On July 12, 1955, just a day prior to her scheduled execution, Ruth Ellis departed from her initial legal counsel, Bickford. Instead, she engaged in a discussion with solicitor Victor Mishcon and his clerk, Leon Simmons. Ruth Ellis sought Mishcon and Simmons’ assistance in drafting her will. When they inquired further, she requested their assurance that her revelations would not be exploited to seek a reprieve; however, Mishcon declined to make such a promise.

During their conversation, Ruth disclosed that Cussen had provided her with the firearm and instructed her in its usage during the weekend preceding the murder. She also revealed that Cussen had driven her to the location of the crime. After a comprehensive two-hour interview, Mishcon and Simmons reported the details to the Home Office. This led to the summoning of Sir Frank Newsam, the Permanent Secretary, back to London, who then directed the head of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to investigate the veracity of Ruth’s claims.

Lloyd George later acknowledged that the police had conducted extensive inquiries, but these efforts did not sway his decision. In fact, they seemed to accentuate Ruth’s culpability by indicating premeditation in the murder. He also cited the injury sustained by a bystander as a pivotal factor in his decision, noting that such reckless use of firearms in public spaces could not be tolerated.

I have always loved your son, and I shall die still loving him.

Ruth Ellis’s final letter to Blakely’s parents from her prison cell

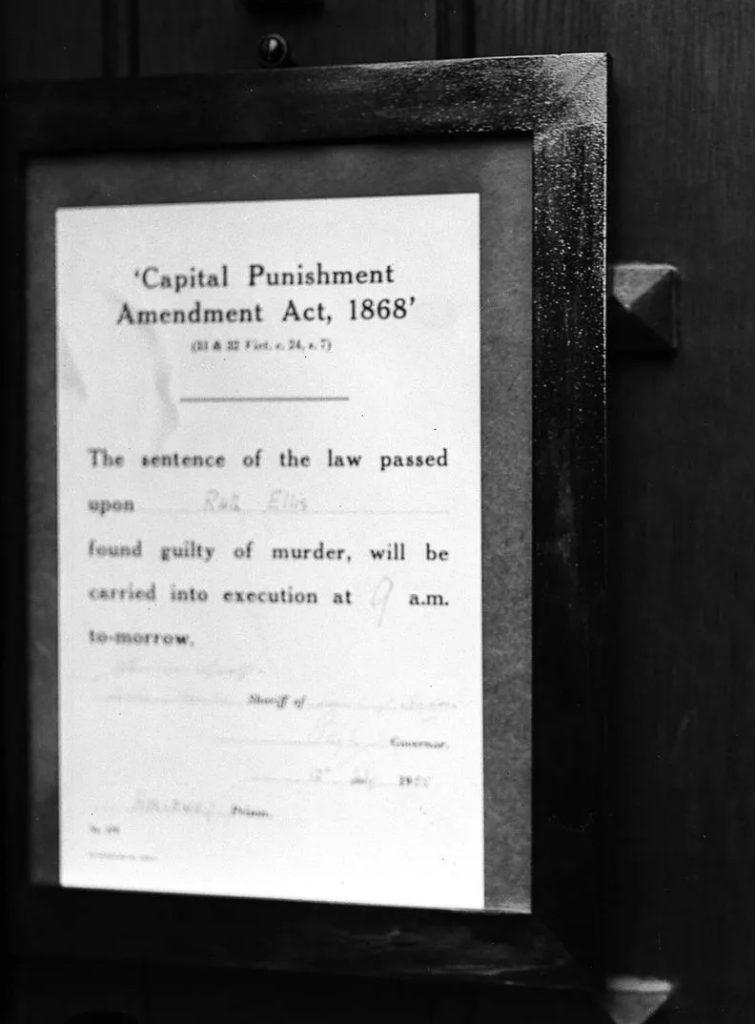

Notice of the hanging of Ruth Ellis on prison door on the day of execution 1955

During that period, a surge of public sentiment emerged, advocating strongly for a reprieve. The groundswell of support was profound, with thousands of individuals adding their signatures to petitions beseeching for clemency.

Even 35 members of the London County Council united in this cause, presenting their impassioned plea to the House of Commons on the very day preceding Ruth’s scheduled execution.

As the evening of Tuesday arrived, marking the eve of the hanging, the Governor of Holloway Prison found it imperative to summon additional police forces. This urgent action became necessary due to a gathering of more than 500 individuals who had assembled outside the prison’s imposing gates.

Crowds gathered outside Holloway Prison

Their presence was marked by a collective spirit, as they sang heartfelt songs and chanted slogans in support of Ruth. This impassioned demonstration persisted for several hours, and the intensity escalated to the point where some among them breached the police cordon. Their aim was to reach the prison gates, where they fervently implored Ruth to join them in prayer.

Inside the usual preparations had been made.

Ruth’s measurements had been taken, and the precise length of the drop meticulously calculated. In anticipation, the gallows underwent rigorous testing on the preceding Tuesday afternoon, using a sandbag mirroring Ruth’s weight. The sandbag was left suspended overnight to negate any potential rope elongation.

As the morning of execution dawned around 7:00 a.m., the trap was reset, and the rope coiled, allowing the leather-shrouded noose to sway just at chest level over the opening. At the behest of Ruth, a cross was positioned on the distant wall of the execution chamber.

Meanwhile, within the confines of her cell, Ruth devoted her time to composing heartfelt letters. An apologetic note to David’s mother for the tragic outcome, and a missive to her solicitor confirming her resolute stance on her impending hanging.

In preparation for the ordeal, she donned canvas pants, a compulsory addition for female inmates post the Edith Thompson episode. The prison’s medical officer provided her with a generous measure of brandy to steady her nerves, while the spiritual solace was offered by an attending Catholic Priest.

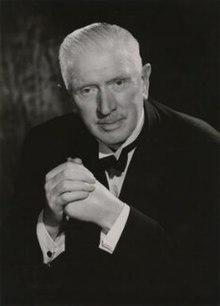

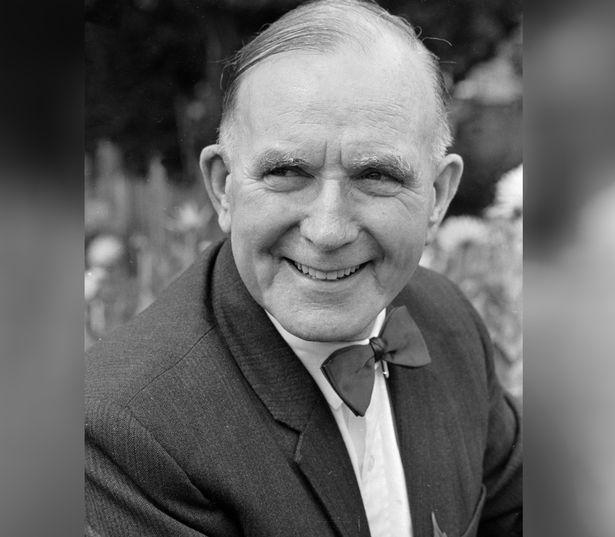

Albert Pierrepoint

At the stroke of nine o’clock, Albert Pierrepoint entered Ruth’s cell, and with his specialised calf leather strap, secured her hands behind her back. He guided her the mere 15 feet to the gallows’ platform. In this moment, Ruth chose silence, offering no final words.

As she stood atop the trapdoor, a cotton hood was drawn over her head, and the noose deftly adjusted around her neck. Assisted by his colleague Royston Ricard, Pierrepoint immobilised her legs with a supple leather strap. The stage set, Pierrepoint removed the safety pin nestled at the lever’s base and with a deliberate push, activated the mechanism, sending the floor plummeting away beneath her.

The event lasted no more than ten or twelve seconds, the process reached its culmination. Ruth’s lifeless form was subjected to a brief examination by the prison’s medical authority before the chamber was secured and she was left suspended for the requisite hour, as stipulated by regulations.

Ruth’s body was removed at precisely 10:00 a.m., and a meticulous autopsy was conducted by the renowned pathologist, Dr. Keith Simpson. The examination revealed that her passing had occurred virtually instantaneously. In a departure from the norm, the autopsy findings were eventually made public. Dr. Simpson highlighted the intriguing detail of brandy being detected in her stomach. The official account of her execution was documented as follows:

Thirteenth July 1955 at H. M. Prison, Holloway N7. Ruth Ellis, Female, 28 years, a Club Manageress of Egerton Gardens, Kensington, London – Cause of Death – Injuries to the central nervous system consequent upon judicial hanging.

Dr. Keith Simpson

Ruth was initially laid to rest within the confines of Holloway prison as mandated by her sentence. However, subsequent to this, her remains were exhumed and subsequently reinterred in a serene churchyard located in Buckinghamshire.

This relocation of her final resting place took place during the reconstruction of Holloway in the 1970s. Notably, Ruth held the sombre distinction of being the sixteenth and final woman to face execution in Britain throughout the entirety of the 20th century.

Aftermath

Ruth’s case ignited a storm of controversy during its time, capturing the public’s imagination with an unprecedented fervour that even reached the highest levels of government discussion, including the Cabinet.

In his memoirs, the then-Prime Minister Anthony Eden omitted any mention of the case, and his official papers also remain silent on the matter. While he acknowledged the Home Secretary’s jurisdiction over the decision, subtle hints suggest that he grappled with inner conflicts over it.

A petition imploring the Home Office for clemency amassed an impressive 50,000 signatures, only to meet the unfortunate fate of rejection.

On the fateful day of Ruth’s execution, Sir William Neil Connor, a prominent journalist from the Daily Mirror renowned for his pseudonym “Cassandra,” passionately contested her sentence. In his words:

The one thing that brings stature and dignity to mankind and raises us above the beasts will have been denied her — pity and the hope of ultimate redemption.

Sir William Neil Connor

Meanwhile, the British Pathé newsreel coverage of the execution boldly posed a thought-provoking question: Can the imposition of capital punishment, whether upon a woman or anyone else, truly find justification in the context of the 20th century?

While the execution garnered general backing from the British public, it significantly contributed to the growing momentum behind the movement to abolish the death penalty. This eventually led to its de facto suspension for murder in Britain, a decade later (marking the last execution in the UK in 1964).

By that time, the concept of clemency had become a prevailing practice. According to a statistical report, spanning from 1926 to 1954, a total of 677 men and 60 women had received death sentences in England and Wales. However, the actual executions numbered far fewer, with only 375 men and a mere seven women meeting that fate.

The ramifications of Ruth Ellis’s execution reverberated extensively, leaving enduring political and heartrending consequences for both her family and her own life story. Tragically, the aftermath of her death cast a shadow that reached deep into the lives of those closest to her.

Following Ruth’s execution, her former husband, George Ellis, tragically took his own life through hanging at a Jersey hotel on August 2, 1958. This event marked a poignant continuation of the sorrow that seemed to surround Ruth’s existence.

In 1969, another blow struck the family as Ruth’s mother, Bertha Neilson, was discovered unconscious in a room filled with gas in her Hemel Hempstead flat. The incident left her forever altered, her ability to communicate coherently stripped away, and her recovery incomplete.

Ruth’s son, Andy, who had been a mere 10 years old when his mother was executed, faced a harrowing journey that culminated in his own tragic death in 1982. This heart-wrenching event unfolded in a bedsit, shortly after he had committed an act of desecration upon his mother’s grave. Notably, the trial judge, Sir Cecil Havers, displayed a recurring concern for Andy’s well-being, providing financial support throughout the years. Moreover, Christmas Humphreys, the prosecution counsel during Ruth’s trial, extended his compassion by arranging and covering the expenses of Andy’s funeral.

In the wake of these successive losses, Ruth’s daughter Georgina, who had been just 3 years old at the time of her mother’s execution, was placed in foster care after her father’s suicide three years later. Tragically, Georgina’s life was cut short by cancer in 2001, at the age of 50, marking yet another poignant chapter in the profound impact of Ruth Ellis’s life and tragic end.