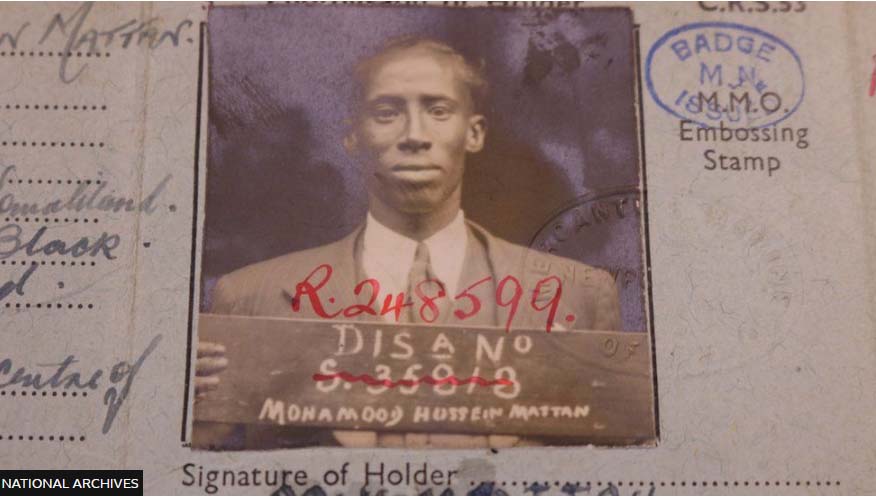

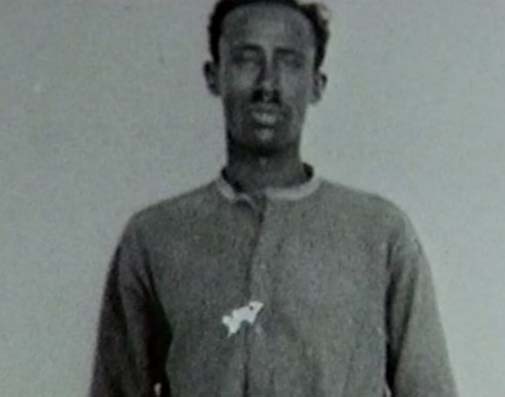

Mahmood Hussein Mattan

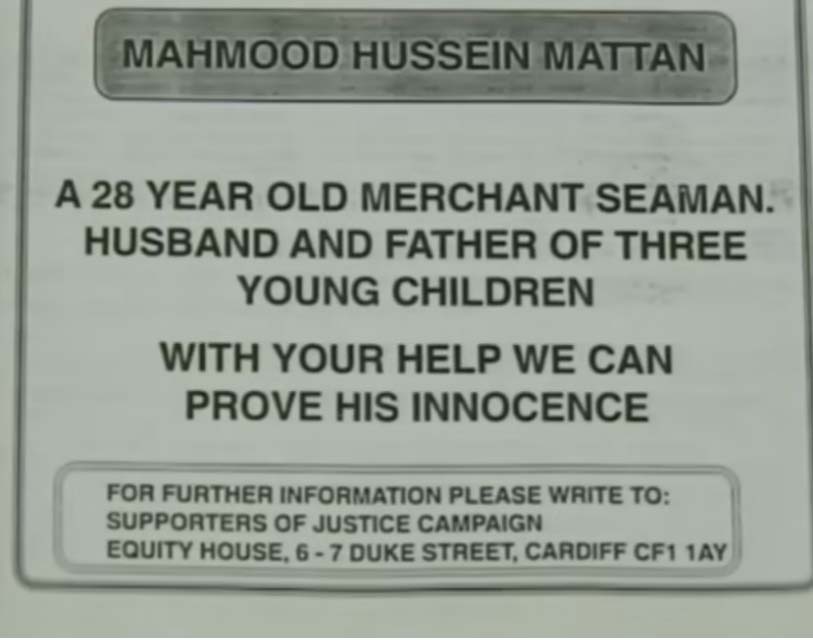

Mahmood Hussein Mattan was born in British Somaliland in the 1920s. It is likely that Mahmood came to Britain while working as a maritime seaman on one of the ships travelling from Africa. Mahmood chose to stay and settled in Tiger Bay in the docks district of Cardiff Wales. By the mid-1940s, Mahmood had settled in Cardiff.

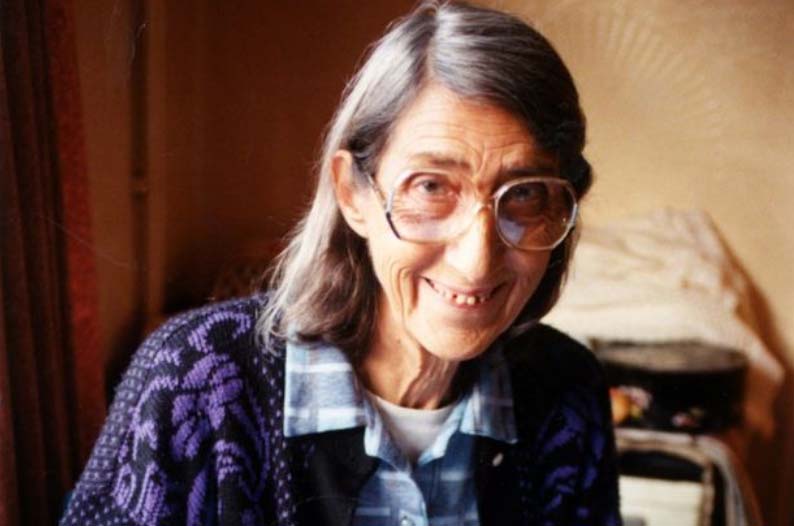

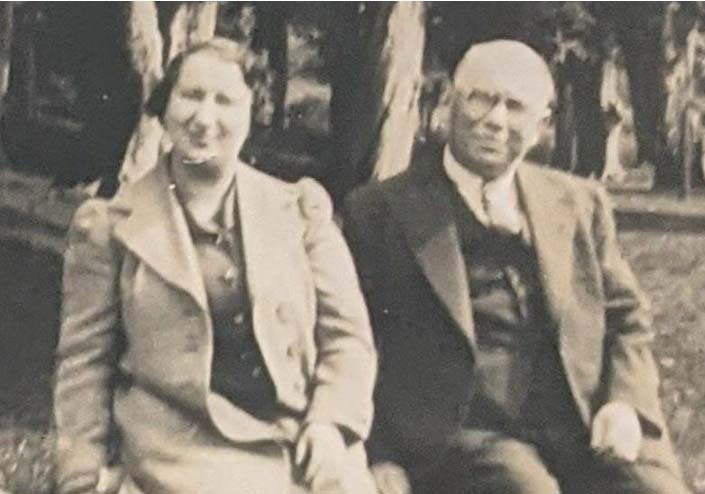

In 1945, Mahmood met his future wife Laura Williams (Pictured) a local woman. One day while she was on her way to work, Mahmood approached her and asked if he could take her to the cinema. Laura was from a white working-class family that lived in the suburbs of Cardiff and she worried that her mother and father would disapprove of their relationship.

Mahmood and Laura fell in love and were married two years later, they looked to find a place to live but facing discrimination no landlord would accept them. Laura continued to live at her parents while Mahmood stayed in his lodging house.

Due to the hardships they faced in Cardiff, Mahmood and Laura decided to move to Hull in East Yorkshire, Mahmood found work and both Laura and Mahmood felt more accepted. However, after a short time Mahmood lost his job and they were forced to move back to Wales.

Soon Laura’s and Mahmood’s family grew, David was born in Cardiff in 1948, Omar in 1949 and Mervyn in 1951. They resided in a house in Davis Street where they were continuously ridiculed for their interracial marriage.

Lily Volpert

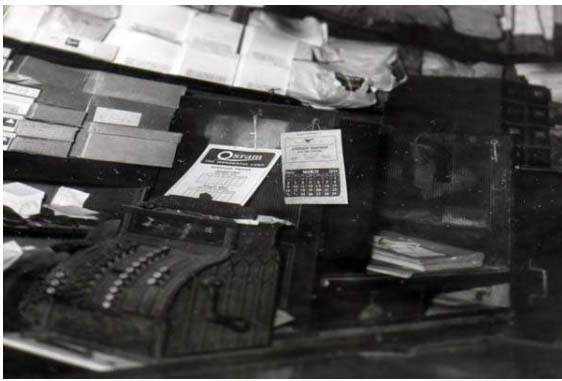

Lily Volpert was 41 years old in 1952, she was the proprietress of Volpert’s an outfitter’s at 203 Bute Street, shop that doubled unofficially as a pawnbroker’s. She lived in the private quarters connected with the shop by a glass panelled door that led from the shop immediately into the dining area, the door from the dining room being directly opposite the front entrance door to the shop. She lived there with her sister, a widow, and her sisters 10-year-old daughter and at the time of the murder her mother had also been there.

The business had been established by Lily Volpert’s father about forty years earlier. Lily had managed the business for a period of about 25 years, after her father died Lily inherited the business.

Murder and Investigation

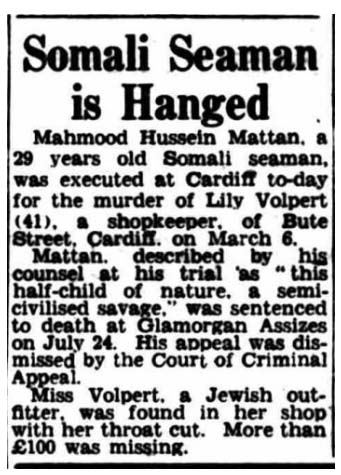

Lily was found dead in her shop at about 8.15pm on 6 March 1952, a man that lived nearby had called at her shop to buy some cigarettes. Her throat had been cut with a razor. When her body was examined shortly after, it was determined that Lily had been killed shortly before being found. The sum of £100 – equivalent to about £3,000 today – had been stolen.

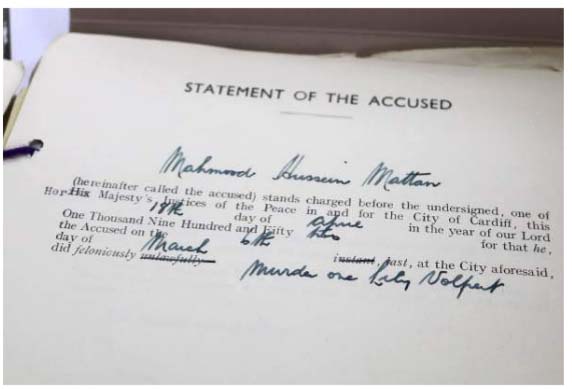

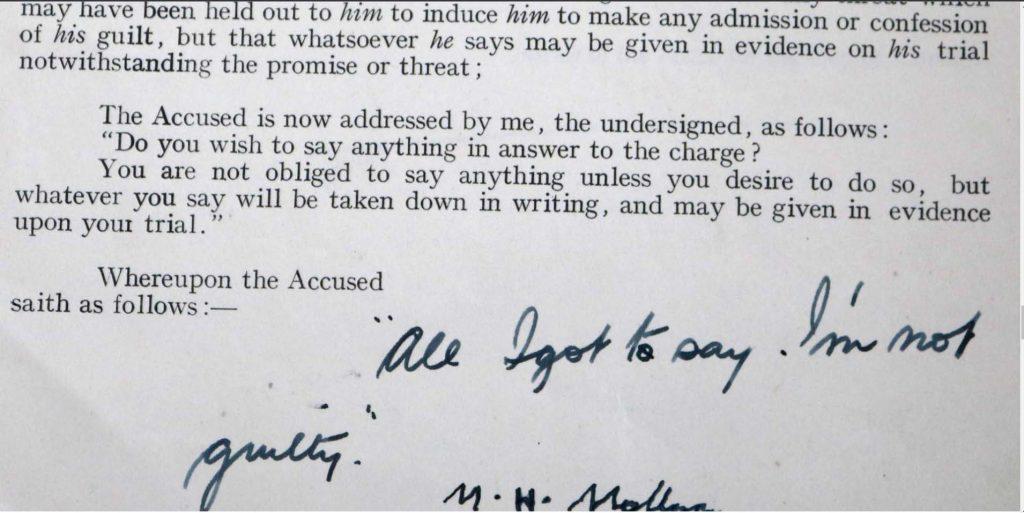

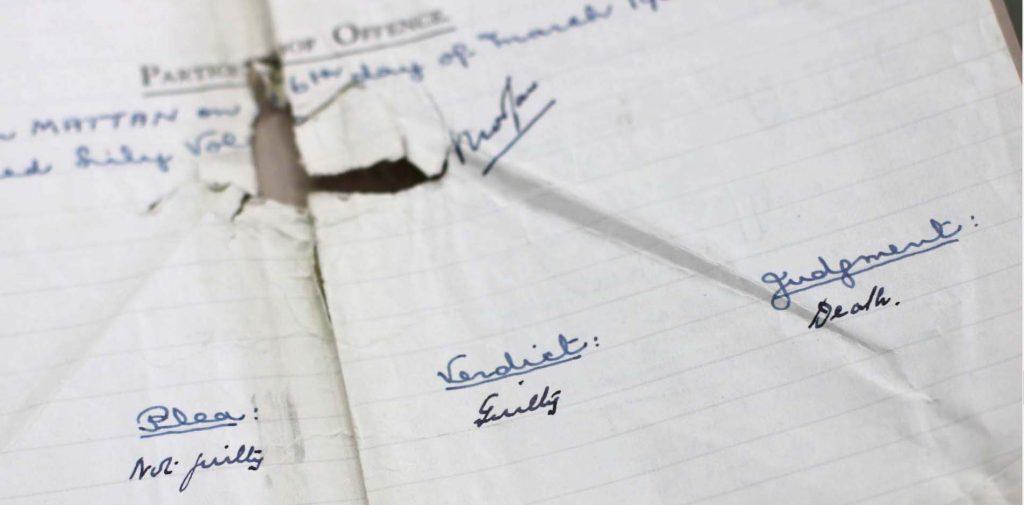

‘All I got to say. I’m not guilty,’ Response to the allegation he killed Lily Volpert

Mahmood Mattan

The police were pressured to act quickly and within a couple of hours they were reportedly looking for a 30-year-old Somalian man, witnesses interviewed reported seeing a seen a dark-skinned man leaving Volpert’s. Many local men were spoken to, including Mahmoud, in order to confirm where they were at between 8-8.30pm on the evening of 6 March 1952. Mahmoud told police he’d been in the cinema on his own, he’d not left until 7.30pm, that he didn’t speak to anyone on his way home and that he’d not been to Bute Street since the previous Sunday. Police searched his lodgings and found nothing suspicious. No evidence of blood-stained clothing, missing money or anything that could have been the murder weapon. Police returned and shortly afterwards on 17 March 1952 charged him with the murder of Lily Volpert.

While in police custody Mahmood featured in at least two police line-ups in which none of the Volpert family picked him out. A 12-year-old girl also came forward to report that she had seen the victim answer the door to a Black man with a moustache after the store had closed at 8pm. This man once again did not match Mahmood’s description as he was always clean shaven. She later gave evidence that when she went to Cardiff Police Station to try and identify the attacker in an identity parade, Mahmood was the only man there. She told the Police that he was not the man she had seen but the they dismissed her, and her evidence was not passed to Mahmood’s defence.

Mahmood was charged with murder. The police allegedly arrested him due to suspected tiny spots of blood on his second-hand shoes as well as the witness statements they had gathered

The Trial

The trial took place at the Glamorgan Assizes in Swansea on 22-24 July 1952. A witness by the name of Harold Cover gave evidence that after leaving a local pub on the night of the murder, he’d made his way to Bute Street and saw Mahmoud coming out of the porch of the Volpert shop at around 8.15PM, the likely time of the killing. The prosecution presented as much evidence as they could to support their theory that Mahmoud was the killer. They presented another witness, May Gray who gave evidence that despite Mahmood being unemployed she had seen him with a wad of banknotes soon after the murder. The prosecution claimed that on Mahmood’s second-hand shoes were tiny specks of blood (although that blood was not forensically linked to the scene), that he had been seen to carry a knife and that he had frequented the Volpert’s shop.

His mother-in-law was called as a prosecution witness who confirmed on the night of the murder he had called at her home a few minutes past 8PM offering to buy her cigarettes. She couldn’t remember what he was wearing but he wore a large black hat, like the one worn by Antony Eden was her best description. The alibi evidence given the day after the murder by Mahmoud was easily undermined and the Crown’s coup de grace was a notice of additional evidence from the cinema manager that the film he said he had been to watch ended at 6.30PM.

Mahmood’s Barrister T E Rhys-Roberts, succeeded in having a large part of the prosecution evidence ruled inadmissible because of the restrictions that then existed on questioning suspects in custody. But in his closing speech he described his client as “this half-child of nature, a semi-civilised savage”. These comments may have prejudiced the jury and undermined Mahmood’s defence. Mahmood Mattan was convicted of the murder of Lily Volpert and the judge passed the mandatory sentence of death.

Mahmood continued with his belief that the guilty person would be found and that he would not be hanged. On 2 September there was an appeal, it was reported in the Daily Mirror reported that the Home Secretary had decided that there would be no reprieve for Mahmood. The following day, on the morning of 3 September, after spending time with an Imam, Mahmood was taken from his cell to the gallows in Cardiff prison and executed. He was the last person to be hanged in Wales. Mahmood’s wife Laura was not informed of her husband’s execution, and only found out when she went to visit him in prison.

“He was convinced they would find out they had made a mistake. He couldn’t speak very good English, but he kept on saying, ‘I kill no woman,’”

Laura Mattan 1997

The Long Road To Justice

Laura Mahmood’s wife along with their three children remained in Cardiff, Laura convinced of her husband’s innocence applied to the Home Secretary, James Callaghan in 1969, asking him to reopen the case when it was discovered that Harold Cover, the prosecutions main witness at Mahmood’s trial, had been sentenced to life imprisonment for attempting to murder a woman, his own daughter, with a razor. Laura was convinced that he was the more likely culprit and had a motive to name an innocent man. The Home Secretary refused to help.

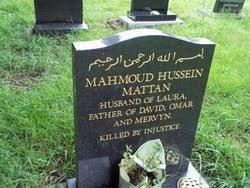

In 1997 Laura and her family, who believed vehemently there had been a miscarriage of justice, asked the newly formed Criminal Case Review Commission to assist. The previous year Mahmood’s family were successful in exhuming Mahmood’s body from a felon’s grave in Cardiff Prison and to have it reburied in the Muslim section of the Western Cemetery in Cardiff. In 1998 Mahmood’s case was referred to the Court of Appeal for re-examination of the conviction. It was the first case ever referred by the Criminal Case Review Commission to the Court of Appeal.

Harold Cover’s evidence that he had seen Mahmoud Mattan leaving the Volpert shop around the time Lily Volpert died was in truth the only evidence against Mahmoud. Mahmoud’s alibi, evidence of knives and the money was only circumstantial evidence produced by the prosecution. Mahmood’s conviction was solely down to Harold Cover’s reliability as a witness and as the CCRC and Appeals Court began to scrutinise him, the concerns about his reliability began to multiply.

The first statement Harold Cover gave to police, the existence of which was unknown to the defence at trial was taken a day after the murder. The evidence that Cover gave at Mahmood’s trial was different. Harold Cover told police the day after the murder he had seen two Somali men, one standing against the glass window and the other coming out of the doorway who passed in front of him. The man who left the shop had a gold tooth and he wore no hat. The man by the window wore a trilby and light mac. He said he would know the man coming out of the shop again but was less certain about the man by the window. He didn’t name Mahmoud and Mahmoud also did not have a gold tooth.

Mahmoud’s name was only eventually offered by Harold Cover as the man he’d seen when a significant financial reward for information leading to the killer was offered by the Volpert family, some of which he received after Mahmoud’s conviction. In addition, it became clear the defence had not been made aware that four people who had been around the shop on the evening had attended an identification parade and not picked Mahmoud out. They had not been told that a 12-year-old girl said Mahmoud was not the man she’d seen at the shop at the time of the murder.

Shortly before the Court of Appeal was preparing to hear the case, an entry in a notebook belonging to a senior office investigating Lily Volpert’s murder was found by the defence. The defence were allowed access to the police notebooks of the investigation. It read: ‘The man seen by Cover was traced – Gass (Taher) and useless? Cover left Cory’s Rest at 7.50pm, identifies the Somali in the porch as Gass.’

The conclusion is that the man Harold Cover both saw but also identified was Taher Gass. In the course of the appeal the Crown disclosed that Taher Gass had been spoken to four days after the murder. Gass had confirmed he lived on Bute Street, he stated that on the evening of the murder he had passed Volpert’s three times the last time between 8.10-8.15PM when everything was quiet. Taher Gass was a 34-year-old Somalian he was tried for murder in 1954 for stabbing Granville Jenkins a wages clerk. The description circulated for Taher in 1954 was disclosed at Mahmood’s appeal, it read

‘DARK COMPLEXION, A MAN OF COLOUR. GOLD TOOTH LEFT UPPER JAW. HAS BEEN CONVICTED OF VIOLENCE.’

Taher Gass was deemed insane in 1954 and sent to Broadmoor. When he was released he was deported to Somalia.

On February 24, 1998, the Court of Appeal came to the judgement that the original case was, in the words of Lord Justice Rose, “demonstrably flawed”. The Court of Appeal outlined their profound regret that this miscarriage of justice had happened and hoped their judgment gave the family a crumb of comfort.

Laura Mattan and her three sons have all since died but South Wales Police have now issued a formal apology to his surviving descendants, admitting the case was “flawed”.

“There is no doubt that Mahmood Mattan was the victim of a miscarriage of justice as a result of a flawed prosecution, of which policing was clearly a part. This is a case very much of its time – racism, bias and prejudice would have been prevalent throughout society, including the criminal justice system. Even to this day we are still working hard to ensure that racism and prejudice are eradicated from society and policing.”

Chief Constable Jeremy Vaughan

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.